Like compressed air, vacuum puts the atmosphere to work. But unlike compressed air, vacuum uses the surrounding atmosphere to create the work force.

Basics Of Vaccum

What is in this article?:

- Basics of Vacuum

- Industrial vacuum systems

- Venturi-type vacuum pumps

- How long to reach maximum vacuum?

For a deeper look at vacuum systems, read “Putting vacuum to work,” “Squeeze energy savings from pneumatic systems,” “Handling vacuum design,” and “Designing with vacuum and suction cups.”

Evacuating air from a closed volume develops a pressure differential between the volume and the surrounding atmosphere. If this closed volume is bound by the surface of a vacuum cup and a workpiece, atmospheric pressure will press the two objects together. The amount of holding force depends on the surface area shared by the two objects and the vacuum level. In an industrial vacuum system, a vacuum pump or generator removes air from a system to create a pressure differential.

Because it is virtually impossible to remove all the air molecules from a container, a perfect vacuum cannot be achieved. Of course, as more air is removed, the pressure differential increases, and the potential vacuum force becomes greater.

|

|

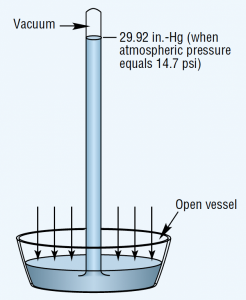

Figure 1. Atmospheric pressure force determines height of mercury column in simple barometer.

|

The vacuum level is determined by the pressure differential between the evacuated volume and the surrounding atmosphere. Several units of measure can be used. Most refer to the height of a column of mercury — usually in.-Hg or mm-Hg. The common metric unit for vacuum measurement is the millibar, or mbar. Other pressure units sometimes used to express vacuum include the interrelated units of atmospheres, torr, and microns. One standard atmosphere equals 14.7 psi (29.92 in.-Hg). Any fraction of an atmosphere is a partial vacuum and equates with negative gauge pressure. A torr is defined as 1/760 of an atmosphere and can also be thought of as 1 mm-Hg, where 760 mm-Hg equals 29.92 in.-Hg. Even smaller is the micron, defined as 0.001 torr. However, these units are used most often when dealing with near-perfect vacuums, usually under laboratory conditions, and seldom in fluid power applications.

Atmospheric pressure is measured with a barometer. A barometer consists of an evacuated vertical tube with its top end closed and its bottom end resting in a container of mercury that is open to the atmosphere, Figure 1. The pressure exerted by the atmosphere acts on the exposed surface of the liquid to force mercury up into the tube. Sea level atmospheric pressure will support a mercury column generally not more than 29.92-in. high. Thus, the standard for atmospheric pressure at sea level is 29.92 in.-Hg, which translates to an absolute pressure of 14.69 psia.

The two basic reference points in all these measurements are standard atmospheric pressure and a perfect vacuum. At atmospheric pressure, the value 0 in.-Hg is equivalent to 14.7 psia. At the opposite reference point, 0 psia, — a perfect vacuum (if it could be attained) — would have a value equal to the other extreme of its range, 29.92 in.-Hg. However, calculating work forces or changes in volume in vacuum systems requires conversions to negative gauge pressure (psig) or absolute pressure (psia).

Atmospheric pressure is assigned the value of zero on the dials of most pressure gauges. Vacuum measurements must, therefore, be less than zero. Negative gage pressure generally is defined as the difference between a given system vacuum and atmospheric pressure.

Vacuum measurement

Several types of gauges measure vacuum level. A Bourdon tube-type gauge is compact and the most widely used device for monitoring vacuum system operation and performance. Measurement is based on the deformation of a curved elastic Bourdon tube when vacuum is applied to the gauge’s port. With the proper linkage, compound Bourdon tube gauges indicate both vacuum and positive pressure.

|

|

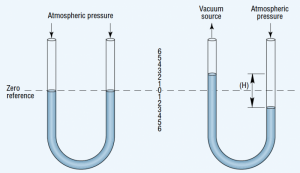

Figure 2. U-tube manometer, filled with mercury, measures vacuum as a difference between vacuum source and atmospheric pressure.

|

An electronic counterpart to the vacuum gauge is the transducer. Vacuum or pressure deflects an elastic metal diaphragm. This deflection varies electrical characteristics of interconnected circuitry to produce an electronic signal that represents the vacuum level.

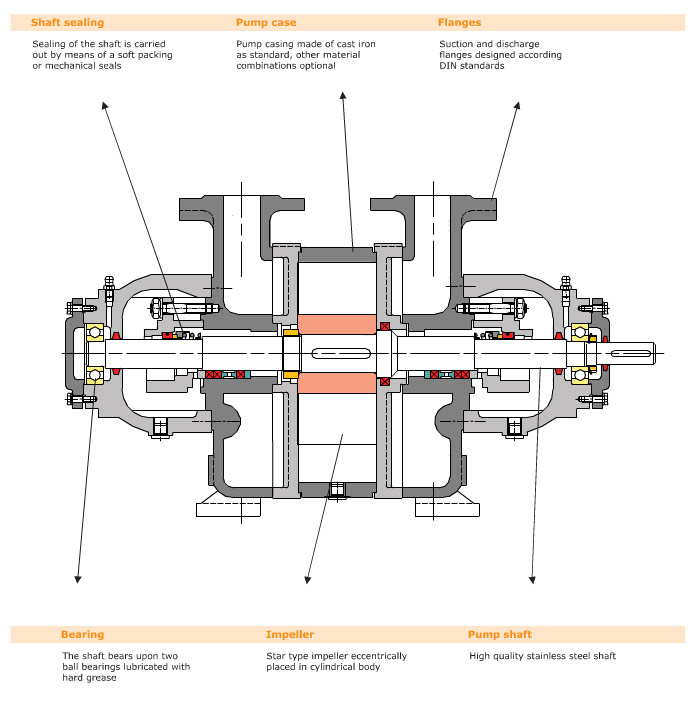

A U-tube manometer, Figure 2, indicates the difference between two pressures. In its simplest form, a manometer is a transparent U-tube half-filled with mercury. With both ends of the tube exposed to atmospheric pressure, the mercury level in each leg is the same. Applying a vacuum to one leg causes the mercury to rise in that leg and to fall in the other. The difference in height between the two levels indicates the vacuum level. Manometers can measure vacuum directly to 29.25 in.-Hg.

|

|

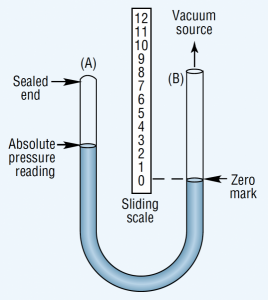

Figure 3. Absolute pressure gauge measures vacuum as the difference in mercury level in its two legs.

|

An absolute pressure gauge shows the pressure above a theoretical perfect vacuum. It has the same U-shape as the manometer, but one leg of the absolute pressure gauge is sealed, Figure 3. Mercury fills this sealed leg when the gauge is at rest. Applying vacuum to the unsealed leg lowers the mercury level in the sealed leg. The vacuum level is measured with a sliding scale placed with its zero point at the mercury level in the unsealed leg. Thus, this gauge compensates for changes in atmospheric pressure.